#

What is it? How old is it? Where did it come from? And what should we call it?

The first time anything like this symbol appears in our history (as we've uncovered it so far) is one of the oldest known abstract marks made by any humanoid, in this case Neanderthals, about 39,000 years ago.

But that's a bit outside the focus of my blog, which is usually related to printing technology. And so that's where we'll pick up this story.

Sharp

The sharp is probably the oldest use of this symbol, although it isn't very clear when it really began to look like #. Originally the sharp symbol (as well as the natural) derived from the same letter "b" that gave us the flat symbol in music (

♭). These symbols developed because in early attempts to record music (around the 12th century or earlier), the note B was the first (and for a long time the only) note that seemed to require modification. To distinguish between the different versions of B they would add a notation using "b rotundum" (the round b), "b quadratum" (square b) and "b cancellatum" (barred b).

I haven't given this a complete study, so I don't know exactly when and how these morphed into our modern flat, sharp, and natural symbols. But around 450 years ago, notation began to use multi-lined staffs to write the notes, often five line staffs but sometimes more. In 1575, Queen Elizabeth granted a printing monopoly to Thomas Tallis and William Byrd as exclusive printers of music. Movable type was applied to the printing of music, and I believe this helped to standardize developing notations. Their early published pieces included flats which are easily recognizable but the sharps looked more like a double X (and nothing at all like any form of "b").

Some forms even looked a bit like a flower.

|

| From A Compendium of Practical Music in Five Parts, 1667, Christopher Simpson (via googlebooks) |

Soon the sharp began to look more familar.

Sample of sharps and flats used in text rather than music, from A Preliminary Discourse to a Scheme Demonstrating the Perfection and Harmony of Sounds, 1726, William Jackson (via googlebooks) |

|

Of course in modern music, the sharp looks noticeably different from the number sign, and in our digital world they're two separate characters, which also differ in appearance. Here they are in this font:

Number: #

Sharp: ♯.

Proofing

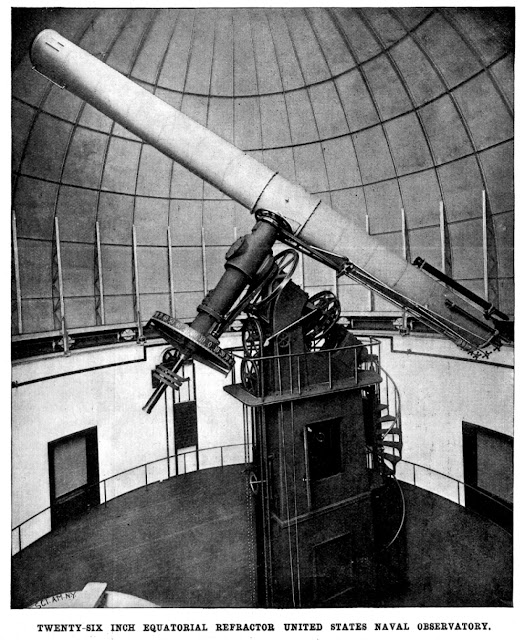

There's one other very old form of # which could be even older than the sharp sign (at least in recognizable form). In the printing process, after a page of text and figures has been "locked up" in a "form", a proof is printed from the form and checked for errors, after which the form can be corrected. There's a standard set of notations for marking these errors for correction (because the corrector is usually not the same person as the compositor). The # symbol is used in the margin to mark lines where a space is missing (and the spot on the line is marked with a caret or slash). This same notation is still in use today. The oldest reference I know of on printing, Joseph Moxon's 1683 text, also describes this notation:

|

| From an 1896 reprint of Moxon's Mechanick Exercises or the Doctrine of Handy-Works Applied to the Art of Printing, Vol. 2, 1693 (via hathitrust.org). |

Of course, Moxon was reporting it, not inventing it, so the usage must be quite a bit older than 1683.

In addition, volume 1 of this reference includes a standard layout for the compositor's cases. The # is used here to mark the sort that other sources say is for spaces or large spaces (bottom row).

|

| From an 1896 reprint of Moxon's Mechanick Exercises or the Doctrine of Handy-Works Applied to the Art of Printing, Vol. 1, 1693 (via hathitrust.org). |

You might think, as I first thought, that this sort was where the number signs were kept, but this isn't so—other sources clearly mark it for spaces. This leads to a question though, where in the case was the number sign? It simply didn't exist as a standard printable character. Perhaps you noticed that in my 1726 image above, the sharps appear to be hand-drawn (or more likely hand-carved characters). Sharps were standard for music printers, but other than that, nothing like a number sign existed in the standard fonts. Of course, many fonts had "specials", and much later on it it became more common for specials to include a number sign, although the exact details are difficult to track down.

Tic-Tac-Toe

Another very old usage for this symbol is as a Tic-Tac-Toe board. In printed descriptions, this is the third oldest form (based on what I've found so far), with a clear description of the game from 1823 under the name "Kit-Cat-Cannio" (

Suffolk Words and Phrases; although they do not reproduce the game board). An 1852 reference shows a game board, as shown below. For reasons that belong in another post, I tend to suspect the game as we know it (and more to the point of this article, the game board) developed during the 1800s or at most the late 1700s.

|

| From The Book of Children's Games, Constance Wakeford Long, 1852 (via googlebooks). |

Number

In 1853 I find this symbol described in a reference as an abbreviation for "number". This is the earliest description of this usage I've found so far. However three years earlier (1850) I've found the symbol used in account ledgers as a pound sign. Which usage came first? Safe bets at this point are that the printed description of number in 1853 trumps pound usage "in the wild" in 1850, because to be described the number usage had to be quite common. And the earliest description of the pound usage I've found is thirty years later. Still, I've barely scratched the surface in references so who knows what might turn up next? At any rate, my assumption now is that usage as "number" is older than "pound".

|

| From An Elementary Treatise on Book-keeping by Single and Double Entry, 1853 (via googlebooks). |

Still, this usage remains quite perplexing. In spite of the above description, I have so far not found any actual usage of it as such prior to the introduction of the typewriter. Many of the sources that mention this usage do so in the context of business (or commerce or retail or something similar). And yet I have still seen no sign of this symbol on old ledgers or inventories or anything of the sort. I don't doubt that examples exist, I just haven't found them yet.

It's also a bit odd that there's no particularly compelling theories on how the number usage originated, even though we have tons of (bad) theories on the pound usage. In print "number" is usually written out, but if it is abbreviated, it is either done as "No.", or as a single character that was apparently not uncommon to printers:

№, as in "№ 2". It's not clear if there's any relationship between the № and # characters, but there is a clear street use versus print dichotomy which I'll cover in more detail in the next section.

Pound

There's a number of theories out there on how this came to be used as a pound sign that all seem to center on confusion between the apparently American number sign and the British pounds sterling sign (£), relating to other technology like the telephone, the typewriter, the Baudot code (the first digital encoding scheme for the telegraph), or other early telegraph codes. The Baudot code theory is by far the most common.

The telegraph system was invented in the late 1830s, more or less simultaneously in the United States by Samuel F. Morse and in England by Charles Wheatstone and William Cooke. By the 1850s this "Victorian Internet" was changing the world. And then in the 1870s, a Frenchman named

Émile Baudot began tinkering with automatic decoding and printing of telegraph signals. To do this, he invented a totally new code, a five digit binary code. The claim is that American and British versions of this code used the number sign and pounds (sterling) sign in the same place. There's a number of problems with this, a big one being that the Baudot code itself was almost never used in the United States. Another big problem is that (despite an unsourced claim in Wikipedia) I can find no evidence that such a code collision ever occurred. At least not exactly. French and British codes overlapped the numero (

№) and pound sterling (£) on the same code (shift-N). However it isn't clear if # ever had dual meaning anywhere in Europe, or if it was an entirely American symbol. Even if codes had overlapped, an obvious issue is that American usage of 12# (weight) and British usage of £12 (currency) are easily distinguished both based on order and context.

But of course the biggest problem is the timeline. The # symbol already had dual meanings by 1853, and almost certainly much earlier. This precludes any technology interference except possibly the original telegraph codes. But again, I find no evidence of collisions (and in fact, no evidence that the number sign had any encoding at all) in any of the common telegraph codes of that era.

This all makes it seem more likely that if there was any confusion or overlap, it went in the opposite direction—documentation of a variety of different national code sets were confused by the pre-existing double meaning of #. Or perhaps, if # was used or known in Europe, the double meaning even encouraged the use of the same code slot for these meanings.

The most popular theory and almost certainly the right one (in my opinion) is that the pounds meaning derived from the common usage of lb as an abbreviation for pounds, or more specifically for the latin "libra pondo". This abbreviation of "lb" or "lbs" was common both then and now, but in addition to the abbreviation, it was also used as a symbol, by crossing a line through the letters like this: ℔. (Some sources distinguish ℔ and lb. as pounds Troy and pounds avoirdupois respectively, however I haven't seen enough consistency across the long span of these usages to say that this is an accurate or useful distinction). This notation goes back at least to Isaac Newton's time, as noted in online sources. Here's an enlarged version of one of his ℔ symbols, together with a sample showing his use in context.

As you can see, in its usual cursive form, it already looks a bit like a pound sign. Note how he has used ℔ as a superscript. I've found this it be a highly consistent usage in handwriting from his time through the 19th century, and one that helps convince me of the # usage when it turns up. It's quite easy to find ℔ in old handwritten receipts and ledgers, as well as "lbs." However use of an actual # is not that common. I first found an 1887 receipt that includes 302 pounds of cheese (shown as 312-10=302) sold at 12 cents per pound for $36.24:

Later I found this example from 1850. It includes two pound signs, although the second one is smudged. It's from a ledger in Hustonville Kentucky from 1850 and includes a line with 7-1/4 pounds of nails, then later 6 pounds of nails.

Early on it's even harder to find it described in a text than it is to see it in use. The first mention in print I have found so far is this 1880 book, where its dual usage as both number and pound is mentioned:

|

| From Book-Keeping by Single and Double Entry, 1880 (via archive.org). |

This mention comes thirty years after I see it "in the wild". Of course it has to be fairly common to be mentioned in a book at all. My assumption is that there was common usage among the people, in markets and in handwriting, where the symbol was long used to mean both number and pound. And then there was

the printing business, dominated primarily by academic concerns, and where these notations would be written out fully, or at least abbreviated in the more traditional printers' way as ℔ and №. These two worlds rarely collided which is why it was so long before this usage was acknowledged. This is supported by the fact that the character used in the above sample seems to be a sharp symbol, not a pound or number sign—they couldn't actually print the literal character in common usage on the streets, because even by 1880 it was still very unusual in typography.

Two technologies seem to confirm this notion: the Linotype, and the typewriter. The Linotype was an extension of printing technologies. The typewriter on the other hand was a replacement for people's handwriting. The first typewriter in 1873 had no number sign (and no lower-case letters for that matter), but by 1886 at the latest, there it was, above the three, right where it is today. Contrast this with the first Linotype that came out in 1886. It had a rack of 72 matrices that could be used to mold characters. None of them was a number sign. But then, by 1906, Linotype had expanded to a 90-character rack of matrices. But still no number sign. It did however have the ℔ symbol. Even by World War II, there was no standard number sign included in most Linotype fonts. (And for the record, they existed, but were extras that had to be added in by hand, rather than from the Linotype keyboard.)

|

| Diagram of Remington typewriter keys, from catalog ca. 1887 (via Harvard Library). |

There's another clue hidden here that's related to the notion of printing versus handwriting. If you go back and look at the full manuscript I linked to for that Isaac Newton reference, he seems to use a form of the ampersand that many still use today—a sort of a cursive plus sign. It's a perfect example of common usage that we can all recognize, and yet it is very rarely mentioned in most printed documents. This is possibly for the simple reason that its representation in typography is very rare. In fact, I'm not even sure that version of the ampersand exists in Unicode. If that form of ampersand can exist for so long without significant discussion, it gives me hope that there are some very old number signs and pound signs out there somewhere, represented as #.

Official name?

So you may have noticed that I have called this symbol a number sign a few times in this post as a more generic name. Today, it's the most common usage (outside of social media of course). It's seldom used to mean pounds anymore. In my opinion, because of the widespread use of the symbol in this context, together with a long history as the same, "number sign" is our best bet as a name for this symbol.

But you may be wondering about a couple of other common names. One of them, the octothorpe, has at least two origin stories, both linked to different sets of employees at Bell Labs around 1963. One of them is almost certainly close to the truth. In 2014, one of the claimants wrote a pretty

detailed piece on the history. But even the authors didn't seem to want it to catch on, and for the most part it hasn't. Despite a few sources that call it the "official" name, this seems to have been little more than a joke.

Which brings me to the other common name, the "hash", or "hash mark" or "hash sign". I think that one deserves a posting all its own, so you'll have to wait to see how I demonstrate that the British are ruining the English language

in part two.